My Nusechka, –

Thank you for your sincere words Nusechka,

I truly wish for a quick union[i]

(22 April 1936)

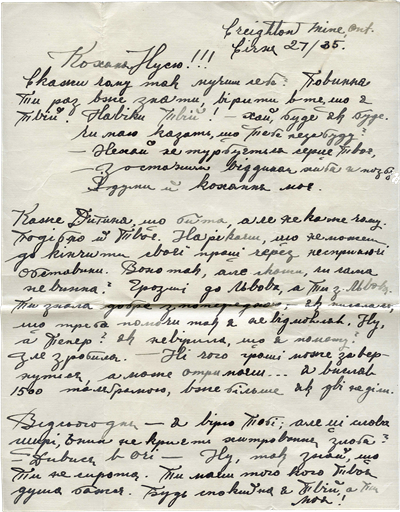

{173}Letters and photographs from the 1930s bring to life the long-distance courtship between the young and beautiful Anna Zabolotna (nicknamed Nusen’ka/Nusechka/Nusia) and the hard-working and industrious Wasyl Kuryliw (nicknamed Vasia). She was living in Ukraine; he had chosen to seek his fortune in Canada. Their correspondence stretched out over eight years, and led eventually to a strong, 65-year marriage. (Fig. 85, 86)

It all began in 1928 when, at the age of 18, Wasyl left their home village of Potochyshche, near Horodenka, Ukraine, and boarded the ship The Empress of France, bound for Canada. At that time, although Anna and Wasyl were the same age, and lived within the same area, they knew each other only in passing. Anna and her family lived in town, providing her with greater educational opportunities. She attended gymnasium (high school) in Horodenka, and later a polytechnic school (university) in Lviv, which was in Poland at the time. Wasyl, on the other hand, had to pitch in and to help on the family farm; he only completed the equivalent of Grade 3 schooling. They would have met in town and possibly socialized at youth-related activities in the village, but the difference in their social status kept them from mingling in the same circle of friends. At that time, some felt that Wasyl was not the perfect match for Anna.

{174}Wasyl was motivated to better his situation. He arrived in the New World with $5 in his pocket, a limited education, and a huge supply of optimism and zest for life. He first made his way to Saskatchewan to work as a contract farm labourer. However, the “promised land” soon became less promising. The Depression years were not easy for most Canadians and even less so for new immigrants. Wasyl was one of many young men who rode the rails across the prairies. At some point, he decided to travel back east, and for a time worked in lumber mills as a water boy for five cents a day near Fort William, Ontario. Fortunately, Wasyl was then hired in the early 1930s as a miner for Inco at the Creighton Mine in Sudbury, Ontario.[ii]

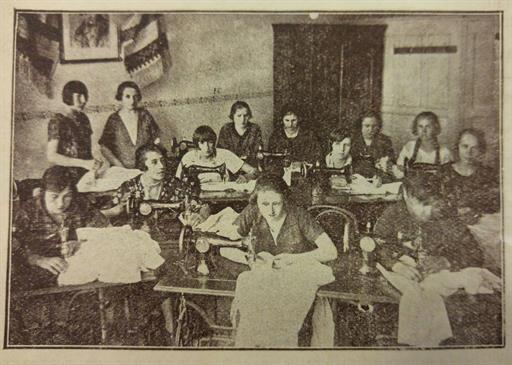

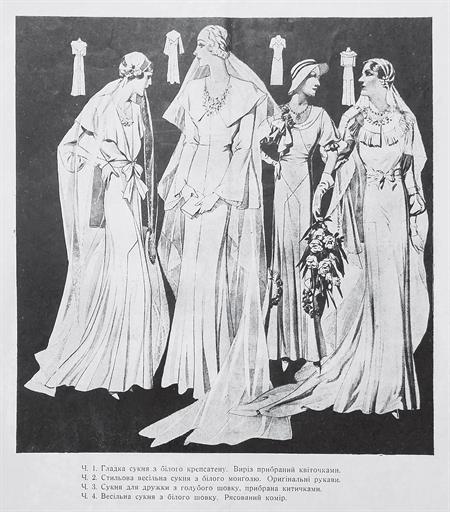

During those years Anna continued her high school studies in the town of Horodenka and was very active in the local folk art collective and sewing circle in Potochyshche. Sewing circles (Fig. 87) were first established in the 1920s by the Союз українок (Union of Ukrainian Women).[iii] The women worked closely with the Просвіта (Enlightenment), Рідна Школа (Native School), and Сільський господар (Farmer) societies that had been founded to improve lives in the rural communities. The women’s group supported village libraries and learning centres where young women were exposed to the latest literature and could hone their writing skills. They also offered training courses on topics such as operating co-operatives and nursery schools, housekeeping and gardening, and personal hygiene. In addition, there was a great emphasis on teaching practical trades such as pattern-making and sewing, as well as the folk arts of weaving and embroidery. The goal was to promote independence and self-reliance among the women in the villages.

It was through the sewing circle, and the school program, that Anna Zabolotna learned to sew and embroider. In her school photo (Fig. 88) we see the students proudly wearing their embroidered clothing, and Anna is holding on her lap a very unique embroidered clutch purse that she made. Sewing circle participants typically met on a regular basis for the purpose of learning and practicing their skills, all the while discussing personal issues and local politics, as well the latest literature authored by Union of Ukrainian Women leaders. Through the sale of needlework, they would also support charitable causes in the community.

Wasyl was a very conscientious man, who cared for the community that he left behind in Ukraine. We learn from his early letters that he began his correspondence with Anna, and her aunt “Mrs. Zabolotna,” by sending money to support the local folk art collectives and sewing circle in Potochyshche.

{176:large}{178:large}

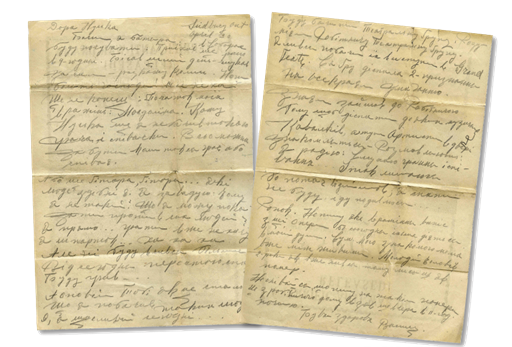

The eight letters that Anna saved, include six letters that Wasyl sent to her directly, one from Wasyl to Mrs. Zabolotna, and a postcard that Anna had sent to Wasyl. In one of the earliest letters, dated 30 January 1934, we are made aware that Wasyl had already been corresponding with Anna for some time and had previously sent money in increments of $5 and $10 that were to be forwarded to the teacher and sewing circle instructor. In a later letter to Mrs. Zabolotna, dated 12 September 1934, Wasyl makes reference to a forthcoming sum of $100 that was collected from “donors,” suggesting that he had inspired others to contribute towards the program as well. The funds were meant to support the purchase of materials and to pay the instructors for their time.

Creighton Mine, Ontario

September 12/34

Mrs. Zabolotna!

…The matter is such: a needlework course took place at your house;

…I have some money left over and I would like to send it to those who deserve it [for teaching the course]. All the donors have agreed that we should send you $100. I will send it to you today. From myself I thank you!...

I remain with respect

Wasyl Kuryliw

In many cases, a long-distance relationship provided an opportunity to get to know each other slowly. It was also somewhat exotic and provided an outlet to vent personal frustrations with someone outside the immediate circle of family and friends. Although Wasyl and Anna were physically thousands of miles apart, their relationship remained strong. As time passed, the correspondence continued and the long-distance relationship matured. Unfortunately, courtship from afar can be difficult. In many cases a couple relies only on visual memories and a few photographs to keep the connection alive; and there are fewer shared experiences that provide a chance to build a strong relationship. It is not known if Anna and Wasyl ever exchanged photos, but it was certainly on their minds. In a letter dated 27 January 1935, reference is made to the need for visual connection. Wasyl responds to Anna’s request for a photograph: “You have asked me several times for a photograph. I cannot send You one right now, because I do not have time to have one taken. I am the same as I was, unless older – more wrinkles on my forehead. I will send one to you sometime. Well, and You yours? – You don’t have one?”

Although the letters we have are sent primarily by Wasyl, we can ascertain that the two of them did exchange personal information about themselves and their social activities. On 27 January 1935, Wasyl asked Anna, “What do you want to know about me?” and replies to his own query,“I am studying. I have a Kobzar, From the Heights and the Depths and so I slowly learn these treasures. Not long ago I received [an] Anthology of Ukrainian Poems. A collection of poems, starting with ‘The Tale of Igor's Campaign,’ all the way to Franko.”

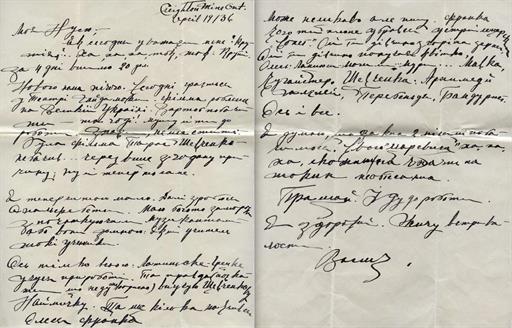

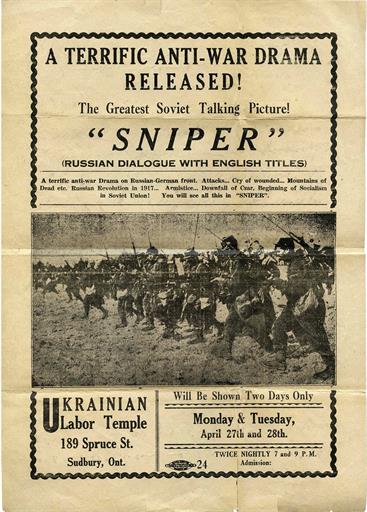

Wasyl also reaches out in several letters, offering insight and information on the activities in Sudbury, Ontario, including local plays and movies that were hosted at the “Labour Hall.”

Today Haidamaky is playing at the theatre. The film was made in Central Ukraine. It would be worth seeing – but it is impossible! I have to go to work. You know, it doesn’t work out: There was [also] a Taras Shevchenko film – I didn’t see it [either] because of the aforementioned reason… (19 April 1936)

I am going to see a theatrical group. You understand a Labour Theatrical group. I stayed behind to see their performance at the Grand Theatre. They received second prize at the national competition ... Do not be angry that I am writing on this type of paper [poster from the movie Sniper], I took it from the Labour Hall yesterday at 11 at night. (April 30, 1936) (Fig. 89, 90)

{180:large} {181:large}

Wasyl also requests that Anna fill in details about her own current affairs: “Write what You and your brother were speaking about? What is new and the like.” (30 January 1934)

There was definitely an effort by both Anna and Wasyl to invite and involve each other in a more close and friendly relationship, albeit long-distance. From Wasyl’s letters we learn that the information in Anna’s letters must have been of a more personal nature. Anna was the eldest of five children. Her parents had both passed away before she turned 24, leaving her alone with the responsibility of the family. Wasyl’s replies to her letters are compassionate, and provide comfort and encouragement as Anna deals with the loss of her mother and financial issues:

Look in [my] eyes … and then know that you are not an orphan. You have the one that your spirit desires. Be at peace, I am Yours and You are mine! ...You cry, why do you spill your pearly tears? O, my [dear], how I would want to wipe those tears from Your eyes. Nusia, my heart, do not cry!

You complain that you are not able to finish your work because of unfavourable circumstances. That is that…but say you are not to blame. You knew from before, when you wrote [saying] that you needed help, I did not refuse. And now? How can you not believe that I will help you [once again]? Well, it doesn’t matter, the money might be returned, or you may still receive them. I sent 1500 by telegram over three weeks ago. (27 January 1935)

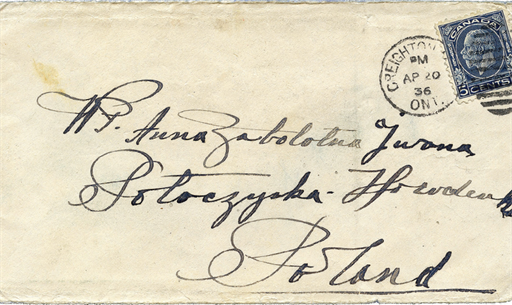

From the correspondence, it is obvious that the postal service was not reliable in Ukraine. Through Wasyl, and his response to Anna’s situation, we experience the sense of frustration and urgency she conveyed regarding missing funds that Wasyl had promised to send. Would mail and money be returned? Would it be received? The situation was not unusual at that time. The typical delivery time of mail from Eastern Europe to Canada during the 1930s was approximately one to two weeks, depending on whether it was addressed to Eastern or Western Canada.[iv] On the other hand, mail posted in Canada took considerably longer to reach a destination within any region of Ukraine, especially a small town such as Potochyshche. The long distance definitely contributed but was also compounded by internal issues. As Ukrainian political boundaries continued to fluctuate in the early twentieth century, it is documented that between 1918 and 1939, postal stamps were reissued and procedures were modified over 50 times. The processing was not consistent. Stamps on Wasyl’s envelopes indicate that, during the peak of correspondence, his letters were first processed within the Polish system before reaching Anna. And many are suspected not to have made it into Anna’s hands at all.

(Fig. 91, 92, 93) {182:large} {183:large}

Although postal service was poor, it was the lifeline of Ukrainian nationalistic messages within Europe and abroad. It was the distribution point for letters, newspapers, and telegrams to family, friends, and communities all over the world. Wasyl had taught himself to read and write and had developed a voracious appetite for Ukrainian literature. In his letter of 30 January 1934, he makes reference to receiving a list from the Enlightenment Reading Society.[v] The Society’s mandate was to make information in Ukrainian accessible, and the society accommodated requests from Canada by sending lists of available titles that could be ordered from abroad. Anna must have questioned Wasyl’s support of the Society, and members that may have been mocking him, but Wasyl responded with a positive outlook: “You warn me that I should not send money to the Enlightenment Reading Society. I know why. There are people [there] that laugh at me. [But] let them not kill that [good] within me that would make me stop doing good things.” (January 30, 1934)

{184:large}In a 1914 edition of Як писати листи (How to Write Letters),[vi] we learn that the act of conveying thought from one mind to another through the medium of written language is an art form in itself. A good letter is the result of much forethought and concentration. Not only are every word and phrase meaningful, penmanship, spelling, grammatical construction, and ease of expression help define the author of the letter. Wasyl Kuryliw’s letters were not only rich in language, but they also transmitted many other aspects of his life through the pen and paper of each of his notes.

By sharing his love of literature with Anna in his correspondence, particularly the works of Ivan Franko, we learn two things about Wasyl. First, we find that he was thrifty and frugal; his letters were written on any scrap of paper he could find, such as the ‘Sniper Movie’ poster, and letter pages that were unmatched in size and shape. It was a practice he continued throughout his life as he transcribed Franko’s words wherever and whenever he had time. And second, there was his fascination with poetry, which Wasyl included in several letters to make a point. As couplets, or sonnet, or other poetic forms, poetry within his letters speaks to Wasyl’s tender nature and social sensitivities:

{186}27 January 1935

Let not Your heart trouble itself

If, with my last breath I will lose

My thoughts and my love. (Fig. 94, 95)

Wasyl’s penmanship has also given us clues as to his character. When looking at his earliest letters, in comparison to later messages, specifically the signatures, there is a notable evolution in his handwriting and style. Knowing that he left Ukraine with very little education and limited literacy, and that he frequented the Ukrainian Labour Temple, there are two possible scenarios. Wasyl could have been one of many who attended small workshops, letter-writing tutorials that were offered at the hall; or equally plausible, the first few letters could have been scribed by a letter writer, which was common practice at that time.[vii] Either way, we know that he became a prolific writer; he appreciated the written word and continued to enjoy writing by hand into his later years.

{188:large}Anna saved only eight letters, and there are obvious gaps in correspondence where some major discussions had to have occurred. What is known of Anna and Wasyl’s courtship is that at some point in time Wasyl sent money specifically to pay for a Singer sewing machine for the sewing circle in Potochyshche. And, on that very machine Anna sewed her wedding dress, and most likely designed and embroidered it herself as well. It was in the style of the contemporary white wedding dresses that were popular in Paris and Prague in the late 1920s–early 1930s. By the turn of the century, the white wedding dress had firmly established itself within European tradition. The style itself continued to follow fashionable dress silhouettes of the time; the shorter flapper dress was popular in the 1920s, and the bias-cut fashions were trending in the 1930s. Popular Ukrainian fashion magazines, such as Нова хата (New Home), were published out of Lviv and featured the latest trends created by young designers who had studied in the west. (Fig. 96, 97)

{189}Anna Kuryliw would have had access to magazines and design ideas through the sewing circle and the Union of Ukrainian Women. She chose to make the dress out of a fine white silk. It was ankle length, with a dropped bodice, that featured an embroidered shoulder cover with white on white large petalled flowers around the edges. The final touch was a sheer white veil, held in place by a floral tiara. Anna was a proficient seamstress and designer, sewing for herself and others. However, the wedding dress was one of the few pieces of clothing that she brought with her to Canada. (Fig. 98)

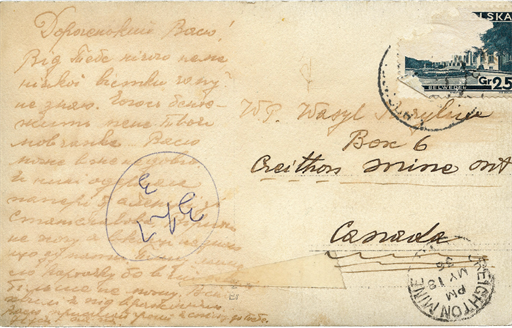

At some point in their long-distance relationship, Wasyl and Anna must have decided that it was time for her to emigrate. In April of 1936, Wasyl responded to one of Anna’s letters – “Thank you for your sincere words. Niusechka, I truly wish for a quick union.” He sends word that he has initiated paperwork and purchased the ticket for her journey to Canada, “The Shifkarta (boat ticket) has been paid up 2 weeks ago. I am sure you will be informed about this,” and notes that, “Now I have finished my part, how soon You will be here – I don’t know. But judging by others, after 2 months you should be departing.” Unfortunately, we learn of Anna’s fears and frustration when later in May she sent a postcard:

{191:large}May 1936

Dearest Vasia!

There has been nothing from you, no word – Why? I don’t know.

Your silence disturbs me somewhat…

Vasiu, perhaps it will not be long.

Today I received papers from an agency in Stanislaviv,

I don’t believe it, and in the end I don’t know what to think.

I am writing you this small card because I cannot … anymore.

At this time, I am convinced that I am [on my way] to [see] you.

Vasiu, send money.

Nusia

{193:small}This post card is the last piece of correspondence between Wasyl and Anna, and the only piece from Anna that Wasyl actually kept. But there was no need for more. Not long after that postcard was sent, Anna began her long journey to Canada. She arrived in Quebec City aboard the Montrose on 24 June 1936. Less than two weeks later, on 5 July, they were married in Sudbury, Ontario at St. Mary’s Ukrainian Catholic Church – Wasyl in a new black suit, Anna in the wedding dress sewn on the Singer that he had funded by mail. (Fig. 99)

As was tradition at the time, in Ukraine and Canada, the groom wore a boutonniere with a long white ribbon.[viii] It was often made by the bride and bridesmaids at the vinkopletennia—a pre-wedding, wreath weaving ceremony.[ix] Anna wore a very delicate veil and wax flower tiara that may have been from Ukraine, but its style was also very popular in North America and could have been purchased upon her arrival in Sudbury.

{194}The postal systems that linked the two countries maintained relationships between family and friends and in many cases helped preserve national and cultural identity. The long-distance courtship by mail between Anna and Wasyl is a beautiful example of the evolution of a relationship between two people living an ocean apart. It also reflects the tensions related to immigration and resettlement in a new country.

Anna kept the letters from Wasyl in the embroidered purse that she had made in school; it was where her daughter found them after her mother’s death. Today, with the advent of e-mail and air travel, global distances seem so much shorter. But in the not-so-distant past, the mechanisms of maintaining personal relationships were few and hardly instantaneous. Anna’s small handful of letters represent a very meaningful and significant part of her life together, yet apart from her beloved Wasyl. (Fig. 100) {196}

[i] Letter from Wasyl Kuryliw to Anna Zabolotna, 22 April 1936, the Kuryliw family Archive.

[ii] Chapters and Verses. DVD. Directed by Oksana Kuryliw and John Leeson. Toronto: Jookjoint Productions, 2016.

[iii] L. Burachynska, “Union of Ukrainian Women,” in Encyclopedia of Ukraine, ed. Danylo H. Struk (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 1993), v. 5, 507–509.

[iv] K. Lemiski, “Ukrainian Government-in-Exile’s Postal Network,” in B. Elliot, et al, Letters across Borders: The Epistolary Practices of International Migrants (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 248.

[v] Bohdan Kravtsiv et al., “Prosvita societies,” in Encyclopedia of Ukraine, ed. Danylo H. Struk (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press,1993), v. 4, 245–52.

[vi] Iasenivsʹkyi, Letter Writer/Ясенівський, Листовник, 7–8.

[vii] The Association of United Ukrainian Canadians in Sudbury, Ontario, was originally known as the Ukrainian Labour Temple. It opened its door in 1928 as a cultural centre, hosting activities for Ukrainian immigrants; helping ease their labour aches and pains, and their feelings of loneliness and their nostalgia for family left behind. Members could also receive help with correspondence to the Old Country, and there were opportunities to study the Ukrainian language, as well as English.

[viii] Boutonnieres with long ribbons appear in wedding photos in Canada and Ukraine beginning in the late 1920s into the 1930s.

[ix] Nadya Foty et.al. Ukrainian Weddings (Edmonton: Kule Folklore Centre, 2007), 35.